Early Christmas morning, I shut off the alarm and lay in bed, still tired after a late night. My cell phone dinged. Ahh, a daughter checking to see if I were watching NASA’s coverage of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) launch. Events like this are a family thing, shared virtually, often with a toast to celebrate success. I texted back, “Just getting up. Turning on the computer.” Too early for wine, tea was my drink of choice.

What a Christmas gift! After three decades of imagination, development, and global teamwork, the deep space telescope designed to give humanity a glimpse back in time to the beginnings of the universe was ready to launch. The European spaceport is in Kourou, French Guiana, on the edge of the Amazon rainforest near the equator. NASA TV provided stunning images: The Arian 5 rocket towering above the trees. A fiery liftoff. And a final a view of the James Webb, separated from the final stage of the rocket and moving past the earth toward deep space.

Watching broadcasts of space missions is always emotional for me. In 2017, twenty years after beginning its journey of discovery of around Saturn and its moons, the spacecraft Cassini sent its final images as it dove into the planet’s atmosphere. I stopped preparing dinner and gave full attention to my laptop perched on the microwave, streaming coverage. When the last image disappeared and Cassini burned up like a meteor, I cried.

Watching the JWST launch was no different. The scope and complexity of the mission. The passion to explore the universe. The cooperation of thousands of people and space agencies around the globe. The perseverance to work through setbacks. The vulnerability of broadcasting the event despite possible failure. These things stir the soul.

Imagine, a telescope so big that it was folded like intricate origami to fit into the faring that protected it as it punctured a hole in the atmosphere. Imagine, a giant mirror over 21 feet across and a multi-layered sunshield unfolding like butterflies emerging from their chrysalises.

Imagine. Someone did. Lots of people did. Their curiosity, skill, and determination led to the launch of the telescope that won’t stop until it reaches a spot along the sun-earth axis over a million miles away.

Images of the launch and NASA’s informative videos have stayed with me, feeding my sense of wonder. During the past week it drew me to poetry, books, and podcasts that explore in different ways the secrets of the universe, our place in it, and the mystery of faith.

After the launch, I pulled out an old coffee table book, The Home Planet, a collection of magnificent photos and reflections of space explorers who have orbited the Earth. Many wrote of a heightened appreciation of the interconnectedness of all things on earth and the overwhelming beauty of our planet after viewing it against the black emptiness of space. Looking through its pages, I marveled at the evolution of space exploration, culminating in JWST’s million-mile journey. Will its revelations move humanity closer to acknowledging the interdependence of all creation? Will it move those on earth to take better care of the planet? Will this encounter with the inconceivable immensity and complexity of the universe foster humility as well as expand knowledge?

Bill Nelson, NASA Administrator, said after the launch, “The promise of Webb is not what we know we will discover; it’s what we don’t yet understand or can’t yet fathom about our universe. I can’t wait to see what it uncovers!”

I wondered, in my own life, how willing I am to admit that I don’t understand? Not only the workings of the universe, but closer to home, realities at work in everyday life. There is much I don’t know or can’t even imagine. For instance, the history and effects of systemic racism and oppression of the marginalized in this country. Am I delving deeper? Educating myself? How willing am I to listen to the truth spoken by those kept on the edges of society? Do I have the humility to hear, to listen with the ear of the heart? To be transformed by it?

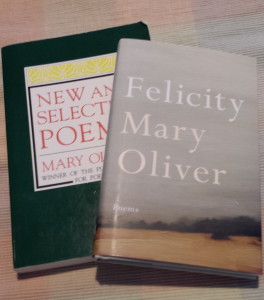

Poetry was my next reading stop. Mary Oliver’s “Where Does the Temple Begin, Where Does It End?” speaks of looking long and deep:

There are things you can’t reach. But

you can reach out to them, and all day long…

… I look; morning to night I am never done with looking.

Looking, I mean not just standing around, but standing around

as though with your arms open…

I imagined the arms of the JWST open wide, gathering energy of the sun. The giant golden eye of a mirror, looking out, slowly gathering in light from billions of years ago. And I thought of my standing with open arms and open heart, ready to receive the Grace of Divine Presence. It’s often not visible or obvious to me, but God is no less present for my inability to perceive. The important thing is to develop a practice of openness “all day long,” never being done with looking.

When it arrives at its destination almost a month after launch, JWST will be carefully positioned in the second Lagrange point that allows it to orbit the sun while remaining in the shadow of the earth. In this place, JWTS’s sunshield will protect it from heat and light from the sun, earth, moon, and even from itself! This is critical for the collection of faint infrared light, a process easily disrupted by other sources of light or heat.

I often think of a comment made by Michael McGregor, author of Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax. When asked if Lax would want others to emulate his life, McGregor was quick to respond. No. What was important to Lax was that people find a place where grace flows for them and put themselves there often.

Grace flows in different places for everyone. Even in different places at different times in a single individual’s life. Putting oneself there is important. The “place” could be simply silence or meditation. Time in the woods, along a beach, taking long walks, or gazing at the night sky. It could be working at a food pantry or homeless shelter, or having conversation with a good friend. Journaling. Painting. We need to spend time in places that shield us from too much “interference” of all types—even from ourselves. To be free of things that hinder the reception of Love, constantly shared, drenching creation.

Sometimes finding that place is not going somewhere. It’s just a matter of turning the heart.

In a conversation with Krista Tippett, Jeff Chu shared some wisdom from the new book he worked on with Rachel Held Evans and which he finished after her death in 2019. Wholehearted Faith was published last month. Speaking about the need for more love, tenderness, and fierce advocacy for justice, he said, “… And so many of us just need a little reminder from time to time that love is there. Love is there if you pay attention. Love is there if you turn your hearts just a little bit.”

Standing under the night sky allows me to “turn my heart,” to open to Love.

In his comments after the launch, Bill Nelson recalled the words of Psalm 19: “The heavens declare the glory of God; the firmament shows his handiwork.”

Indeed, God’s splendor is on display in the stars and galaxies and mysterious beauty of the cosmos. The incarnation celebrated during the Christmas season, this embodied Presence, has inspirited creation from the moment the universe began and continues in every person, creature, and bit of matter here or millions of miles in space.

Just as we cannot imagine how the discoveries of the JWST will affect humanity’s science, spirits, or way of living, we cannot imagine the transforming power of the ongoing incarnation.

The human drive to explore the galaxies, using every bit of human knowledge, skill, and talents is fueled by curiosity and wonder.

Searching our hearts and all that is around us. Paying attention. Looking for the Sacred in our midst. This passion is driven by the longing for meaning, for God, and by the desire to know that we are part of a story far bigger than ourselves. One we can never fully comprehend.

As expressed in Wholehearted Faith, “… many of us have found a renewed sense of possibility when we’ve realized how much of God’s beauty remains to be explored — and that the life of faith is also a life of holy curiosity.”

Thank you NASA and its global partners for an extraordinary Christmas gift, one that reminds us to wonder, to search, and to expect the unexpected. Not only in our universe, but also in our experience of God-with-us.

SOURCES AND RESOURCES

Books

The Home Planet: Conceived and edited by Kevin W. Kelley for the Association of Space Explorers

“Where Does the Temple Begin, Where Does It End?” in Why I Wake Early by Mary Oliver

Wholehearted Faith by Rachel Held Evans and Jeff Chu

Online

OnBeing with Krista Tippet 12/23/21 Jeff Chu: A Life of Holy Curiosity

NASA JWST Sites – Follow links for more information, images, and videos of the JWST

James Webb Space Telescope Homepage

NASA’s Webb Blog where you can keep up with new information

JWST launch: Official NASA Broadcast on YouTube

The poem is “Roses.” Oliver writes of the quest to answer life’s “big questions” and decides to ask the wild roses if they know the answers and might share them with her. They don’t seem to have time for that. As they say, “…we are just now entirely busy being roses.”

The poem is “Roses.” Oliver writes of the quest to answer life’s “big questions” and decides to ask the wild roses if they know the answers and might share them with her. They don’t seem to have time for that. As they say, “…we are just now entirely busy being roses.”

My day was off to a confused start. It was the time change. Usually, the clock by my bed adjusts for moving into or out of daylight savings time, but not this morning. Or maybe I just read it wrong. I hurried, washed my hair, and drove to church. No one was there. That’s when I realized: Daylight savings time was back. Sigh. Not a fan.

My day was off to a confused start. It was the time change. Usually, the clock by my bed adjusts for moving into or out of daylight savings time, but not this morning. Or maybe I just read it wrong. I hurried, washed my hair, and drove to church. No one was there. That’s when I realized: Daylight savings time was back. Sigh. Not a fan.

Bright sun was a welcome change from the grey overcast days we’d been having. I hurried along the sidewalk, passing upscale condos along the street adjacent to the downtown parking lot where my car waits everyday while I’m at work. The brown sandstone cathedral sits just across the street. I thought about dropping in, but opted for the church of buildings and people, cars and cracked sidewalks instead. The cathedral would be locked anyway.

Bright sun was a welcome change from the grey overcast days we’d been having. I hurried along the sidewalk, passing upscale condos along the street adjacent to the downtown parking lot where my car waits everyday while I’m at work. The brown sandstone cathedral sits just across the street. I thought about dropping in, but opted for the church of buildings and people, cars and cracked sidewalks instead. The cathedral would be locked anyway.