My prayer changes as I do and as life does. There are the tried and true: meditation, quiet prayer, old favorites, books of hours, chants. There are communal gatherings and liturgical celebrations. But sometimes, when the world turns upside down, the “order” that I have established prayer-wise disappears. Despite good intentions, I can’t maintain the routine. I blame myself and forget that the spiritual journey is not a smooth, predictable path. (I will borrow from Richard Rohr’s paradigm: order, disorder, reorder.) During this “disorder,”what once brought a sense of connection with the Holy One no longer does. During spiritual dark nights, when the Holy One seems absent, I’ve been counseled to pray through it, to open my heart even when nothing seems to fill it. And so I have.

I remind myself that some of those “dark nights” took months, once even years, to pass. They required trust in my relationship with the Holy One, which, really, is what prayer is all about. Perhaps that is the root of my difficulty with prayer: floundering trust as chaos envelopes the U.S. The hatred, greed, and disregard for law and Constitution is infuriating. Mass deportations without due process and lack of concern for innocents swept up in the frenzy rend my heart. Scrubbing this country’s past of contributions of those who are not white and straight creates an alternative history and implies that everyone else is inconsequential. Removing the immorality and cruelty that has been part of US history glorifies the powerful while dismissing their victims. Truth is one of the victims.

The pushback against the LGBTQ community, particularly the trans community, continues to grow, fueled by misinformation, ignorance, and fear.

The current budget bill passed by Congress is immoral. Slashing programs that serve the poor, the oppressed, and the marginalized in this country and around the world makes no sense. Tax cuts for the wealthiest 1%? Jesus must be weeping.

In this time, I have difficulty “reordering.” I feel spiritually adrift. After sharing this with my spiritual director, we talked about prayer and different ways to frame it.

Prayer is spreading Love energy, she said. It’s resting in God and following God’s Way as best I can. A Christian, I connect that with the way Jesus lived his life. Others will have different understandings, but Love is the root of them all. Standing up for Love. Bringing Love and compassion into this time and place. Standing up for the marginalized. Anyone can do it.

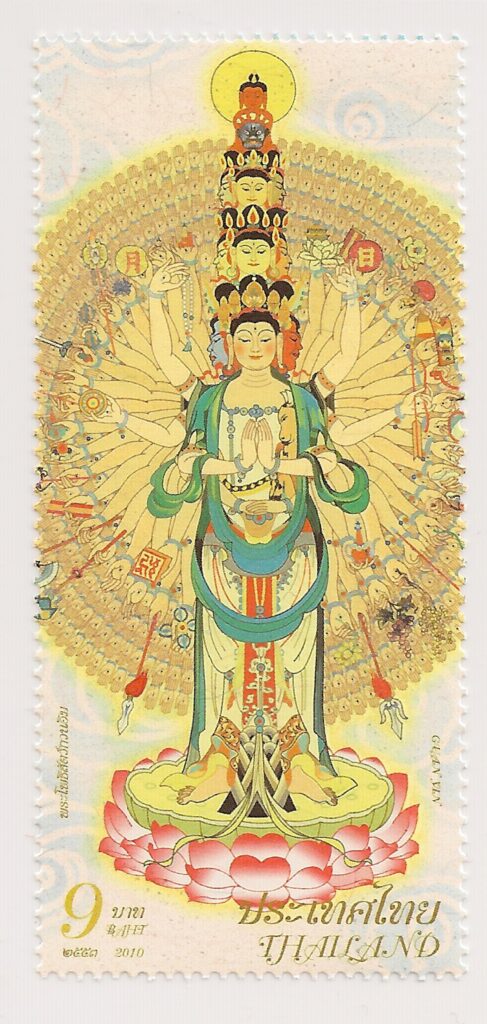

Image of Guan Yin, Buddhist bodhisattva whose name means “Observing the sounds of the world.” She has multiple heads to see and hear those suffering and multiple arms to aid them.

Intention is the key to my prayer these days. I pause and remember I am called to be Christ in the world. Is what I do contributing to bringing compassion into the world? Am I compassionate to myself, taking time for self care so I am able to be present for others? Am I a good “ear” for people who need to tell their stories, listening deeply so they know they are heard and held? Are my letters and calls to legislators designed to defend those targeted with executive orders or legislation that threaten their well-being. To expose harm and hold up morality to those in power and to encourage reflection and change? When I write a column, first I pray that what small bit I have been given to share encourages those who are looking for ways to make a difference.

Christ Has No Body

Christ has no body but yours,

No hands, no feet on earth but yours,

Yours are the eyes with which he looks

Compassion on this world,

Yours are the feet with which he walks to do good,

Yours are the hands, with which he blesses all the world.

Yours are the hands, yours are the feet,

Yours are the eyes, you are his body.

Christ has no body now but yours,

No hands, no feet on earth but yours,

Yours are the eyes with which he looks

compassion on this world.

Christ has no body now on earth but yours.

Theresa of Avila 1515-1582, Spanish Mystic and Carmelite reformer along with John of the Cross.

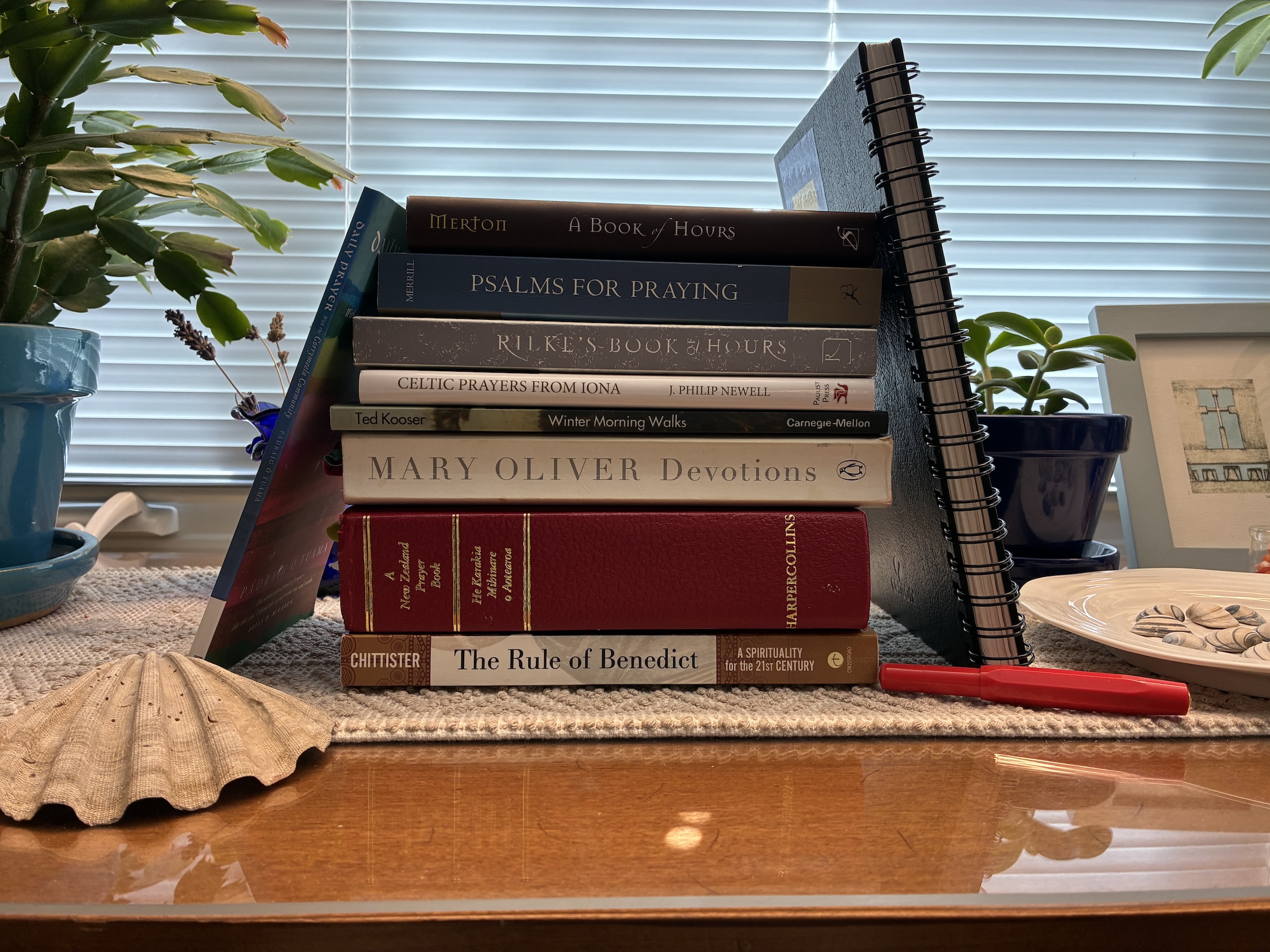

While making an effort to pray with a favorite small book of prayer, Daily Prayer with the Corrymeela Community, by Padraig O Tuama, I am also practicing reframing my understanding of prayer: being intentional about how I live the unfolding day and making sure it is to bring Love and justice into the world. Speaking out as I am able, against the darkness. And trusting in my relationship with the Presence that holds all.

The Civil Rights activists in the 60’s provide inspiration. Their actions were supported by their faith. They weren’t advocating revenge, but respect, equality, and justice. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I have a dream speech” speaks to the unending struggle of those on the margins.

“Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children,” he proclaimed in his soaring oratory. “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.’”

Prayer for me these days is all about intention to be present to Love…and to be Love in the present moment. How it looks day to day doesn’t matter.

Pope Francis also recommended Merton’s openness to God in a contemplative style of prayer. Merton in the midst of a world immersed in “noise” of all types—digital, visual, aural—pouring out of players, electronics, out of the depths of our souls, calls us to quiet presence. For those who fill up every moment with activity and distraction, he says, “Be still. Listen.”

Pope Francis also recommended Merton’s openness to God in a contemplative style of prayer. Merton in the midst of a world immersed in “noise” of all types—digital, visual, aural—pouring out of players, electronics, out of the depths of our souls, calls us to quiet presence. For those who fill up every moment with activity and distraction, he says, “Be still. Listen.”