The feast of Christ the King has rolled around again, and I have decided to do something I rarely do: repost a column. This one, written in the first year of the pandemic, is as relevant now as it was then. Perhaps more so in these days of NO KING demonstrations. I changed the title, added Samuel’s warning to the people’s demand for a king, and deleted reference to the pandemic. I tweaked a bit here and there.

This time, I close the column with the word “kin-dom” rather than “kingdom” because that is the reality Jesus lived and preached—an inclusive, egalitarian community of all people, respecting and caring for one another and the planet with love. He knew that we—along with all creation—are part of the same cosmic kin-dom.

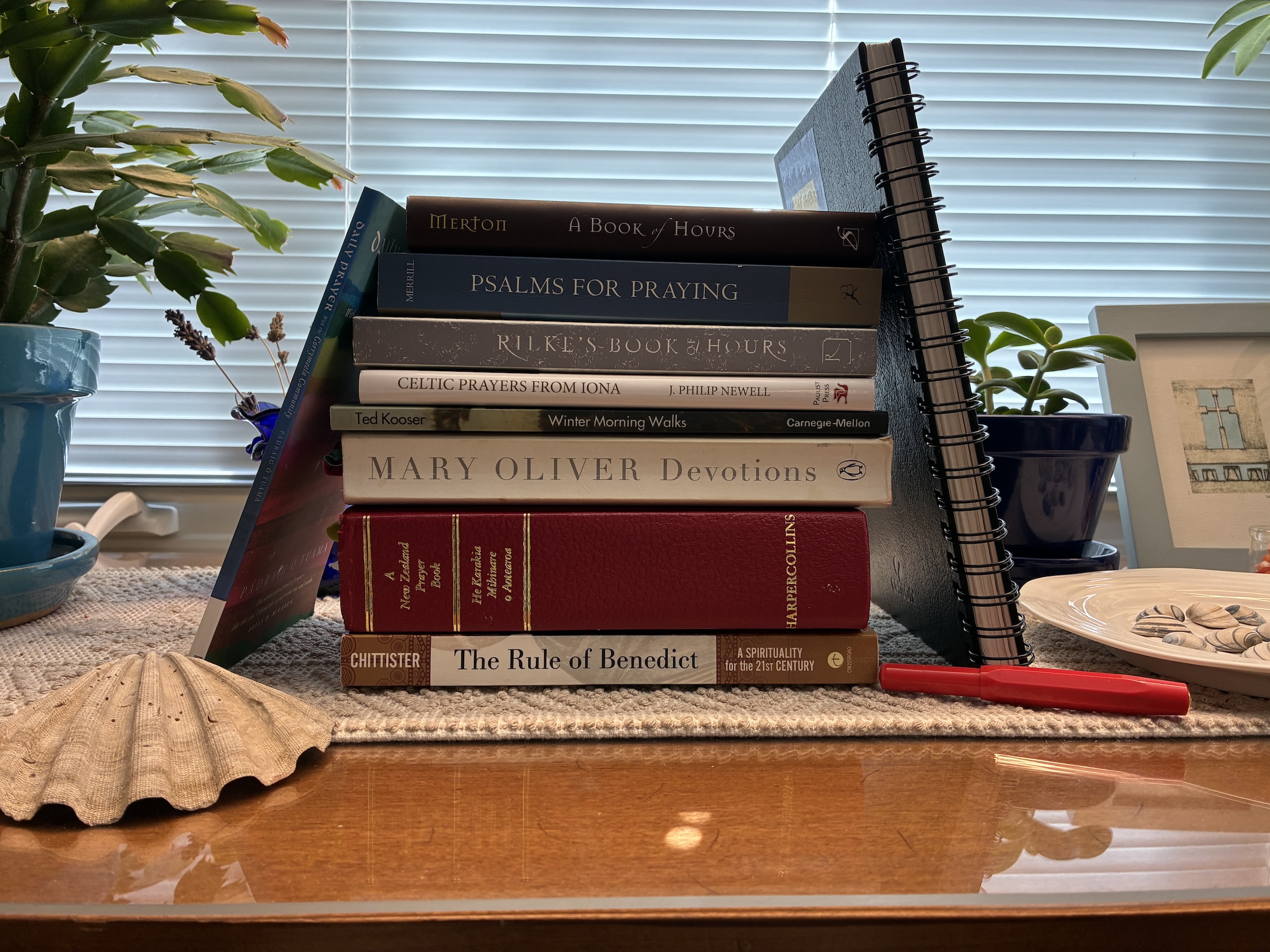

I’ve never warmed up to the image of Christ the King. “King” has too many political overtones. Images of a stern king enthroned and bedecked in robes and a gleaming crown, maybe with one hand grasping a scepter, a symbol of power, have put me off. It seems an odd segue into the celebration of the ongoing Incarnation and the remembrance of Jesus’s birth in poverty.

Kings and kingship have a long history, including the Judeo/Christian tradition. Samuel resisted the people’s desire to have a king:

Samuel told all the words of the Lord to the people who were asking him for a king. He said, “This is what the king who will reign over you will claim as his rights: He will take your sons and make them serve with his chariots and horses, and they will run in front of his chariots. Some he will assign to be commanders of thousands and commanders of fifties, and others to plow his ground and reap his harvest, and still others to make weapons of war and equipment for his chariots. He will take your daughters to be perfumers and cooks and bakers. He will take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive groves and give them to his attendants. He will take a tenth of your grain and of your vintage and give it to his officials and attendants. Your male and female servants and the best of your cattle and donkeys he will take for his own use. He will take a tenth of your flocks, and you yourselves will become his slaves. When that day comes, you will cry out for relief from the king you have chosen, but the Lord will not answer you in that day.” 1 Samuel 8, 10-18

The people’s reasoning – because everyone else has one – seemed shaky. But a king they got, for a while.

I suppose there have been genuinely good kings (and queens) over the centuries, but the associated trappings of power and wealth are hard to overlook. And they corrupt.

In his lifetime, Jesus resisted the title of king, and when people clamored to make him one, he made himself scarce. Of course, the “kingdom of God” is central to his message. But it is a kingdom unlike any earthly kingdom: there is room for all. It isn’t observable. It’s a work in progress, and the progress depends on the people.

It isn’t about exteriority but what’s in the heart, for that is where the kingdom resides, where the Word is spoken and takes root and grows. The signs of the kingdom are love, service, joy, peace, willingness to suffer for the good of others. God sows this Word-seed in human hearts. It has power to grow and transform every person and through them works to transform the world. But how painfully slow is that process!

The kingdom is both/and. Already here and yet to come. “Already here” because the Holy One has placed a bit of Divinity in everyone. “Yet to come” because it must grow with cooperation and surrender.

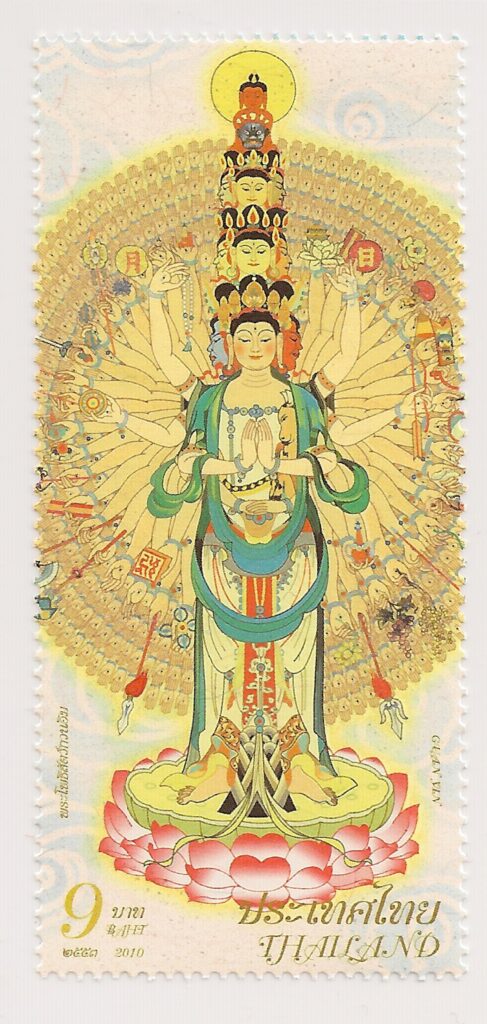

The kingdom is Presence and Possibility. All creation exists in the embrace of the Christ – “The soul is in God and God in the soul, just as the fish is in the sea and the sea in the fish.” (St. Catherine of Siena) All creation, including human beings, is becoming – “Above all, trust in the slow work of God.” (Pierre Teilhard de Chardin)

It is a servant-king that Jesus modeled. He didn’t sit on a throne or live in opulence or control with commands or hang out with those in power. His motives weren’t self-aggrandizement or accumulation of wealth. He didn’t have a place to rest his head. He led by example. The poor and marginalized where his companions.

Jesus was a man of both action and prayer. He preached, healed, fed, walked, and sat with others. And when he prayed, he didn’t sit in a privileged place but more likely on a rock in the wilderness.

In our time and place in a world ravaged by violence, divisiveness, hatred, and othering. A world in political turmoil, the call is to follow this Servant-King. The power to be wielded is that of Love, prayer, and service. Jesus provides a job description in Matthew’s gospel. When he“ sits on his glorious throne,” the criteria for judgement is love in service. Did you feed the hungry and give drink to the thirsty? Did you clothe the naked and visit the prisoners? What did you do to open yourself to Love and then give it away?

If I were asked to create an image of Christ the King, it would be of a person busy taking care of others. Ordinary attire would replace robes and crowns. The scepter would be gone, and if a hand was free at all, it would hold a shepherd’s staff or maybe food to be given away, a stethoscope, a cooking pot, seeds, a pen, a book, a brush. Whatever one needs to be who they are created to be. To do their work in bringing the kin-dom.