This column is more political than my usual offerings. I can’t talk about spirituality as if it exists in a vacuum. Many of my readers will resonate with my thoughts and feelings. Others may not. But I must do what is mine to do.

I began writing this column in September, when I woke up thinking “hope.” Feeling hope. While that may not seem surprising, it was for me. In the middle of election season, I had been living with dread and fear about the future. No matter how deep it’s pushed down or how purposely ignored, fear sucks hope right out of a person. That was me.

What allowed me to throw fear out and embrace hope instead? The Democratic National Convention. Instead of the vengeful rhetoric espoused by some Republican candidates aimed at stirring up fear and keeping us down and apart, there was hope. There was a positive view of the future that included everyone. No hateful misinformation about the transgender community. No disparaging remarks about immigrants or calling for mass deportation. No whitewashing the part race and slavery played (and plays) in U.S. history.

When the cameras scanned the crowd, diversity was everywhere. It was celebrated by those who spoke and in what they said. It seemed possible that this country could embrace compassion and love of neighbor. It seemed possible that we could, together, move in a more positive way through the challenges and tragedies of our world. Perhaps we could believe that we are, indeed, more alike than we are different.

When I woke up on November 6, fear and anger again had replaced my hope, and dread for the future was taking over. The vision of inclusion, respect and moving forward together was replaced by one of negativity, revenge, and disrespect of “other.” The highjacking of “Christianity,” putting it into service of an approach that seems anything but Christian, continues to sweep the country. Efforts to enshrine Evangelical White Christian Nationalism as the official religion of the U.S. is grossly un-American.

I wasn’t alone in my “morning after” despair. Many concerned with climate change heard “Drill, baby drill,” with disbelief. Many concerned with women’s rights heard “Your body, my choice,” with dismay. And basic human rights? Democratic institutions?

Struggling with all this, I listen to many wisdom voices, past and present: my faith and spiritual/wisdom teachers of many traditions; civil rights leaders; psychologists and counselors; poets; good friends. In addition to eating well and incorporating exercise into the day, here are thoughts on getting through these difficult times:

Grieve Alone and Together

Recognize feelings and emotions. Experience them. Feel sorrow, anger, fear, and despair. Weep. Rant. Vent. Sometimes alone. Sometimes with friends who can hold your tears and love you when you’re a mess. Find communities where you can share your grief. When one member has no hope, someone there will. Remember, grief isn’t once and done.

Who are the people, the communities that can hold you, support you, love you? Who are those who share your sorrow? Who are those with whom you can both grieve and find hope?

Find a Place Where Grace Flows

The week after the election found me on Chincoteague Island with my daughter. The ocean draws me into a contemplative space, opening my soul to release emotions – joy, gratitude, grief, sorrow – as well as to receive grace of healing, wonder, and gratitude.

My salty tears mingled with salty air. I rejoiced at the birds’ antics and wondered at shells at my feet. I laughed, prayed, and sang into to the pounding of wave after wave on the sand. Sometimes alone. Sometimes with my daughter. Together we watched the Supermoon rise, the king tide flood the marshlands, and herons wait patiently along the banks until the water receded and they could resume their mindful-walking fishing practice.

My ocean visits are few and precious. I have other Grace places: a small, neighborhood woods; a local café where I go to write; art museums; a friend’s kitchen table; my favorite chair flanked with a handmade table that holds a mug of tea and a stack of books.

What are your ordinary as well as extraordinary places where Grace flows? As Robert Lax would advise, go there often.

Establish a Grounding Practice

Take time for spirit-nourishing practices.

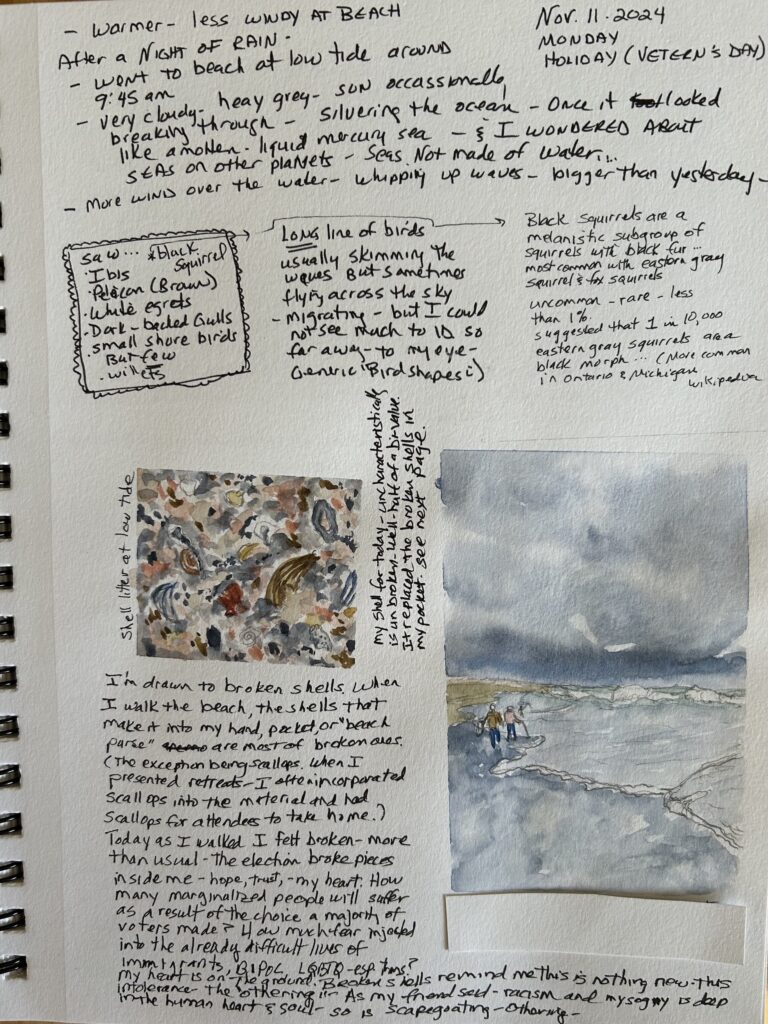

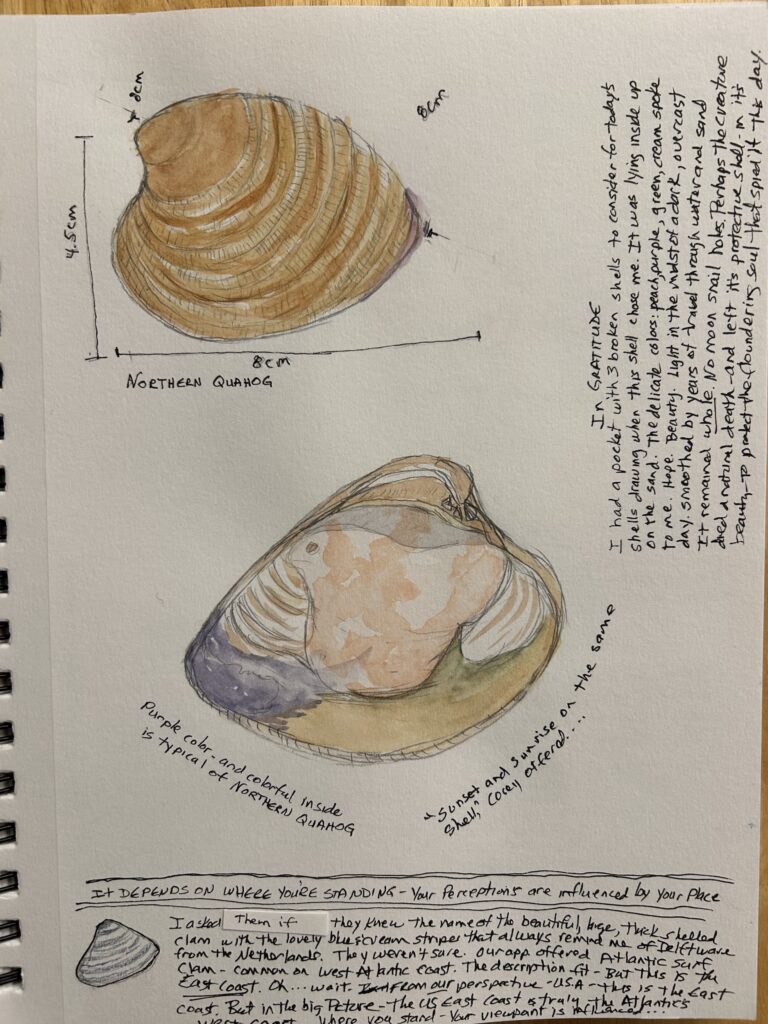

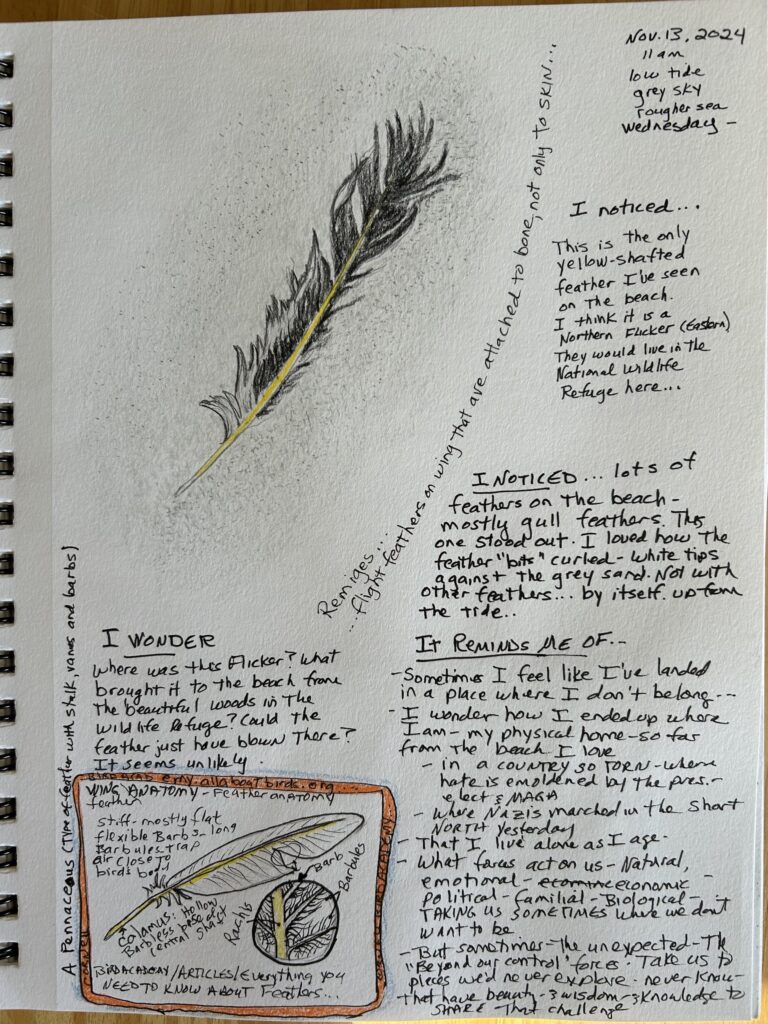

At the beach condo, my daughter set up a long table filled with art and journaling supplies. Every day we showed up there, like pilgrims to a holy place. She painted. I created page after page in my nature journal: mosaics of small drawings, paintings, and words.

Journaling/Art

For some, journaling and creative arts are prayerful, centering activities. While on Chincoteague I didn’t work on my current book project. I didn’t write this long overdue column. Now, back home, those projects call for my attention along with piles of laundry, dishes, and routine chores. While I can’t give hours every day to nature journaling, I’ll try for one day a week. And I can be faithful to my regular journaling practice.

Quiet Time/Prayer

During information overload, refrain from too much news consumption and social media scrolling. Make time for quiet. I’m reestablishing a morning routine of sipping tea, twenty minutes of quiet prayer, and reading.Throughout the day I take a few moments, breathe deeply and remember that I live and move in the Presence of the Sacred, no matter what I’m doing.

Quiet walks around the neighborhood or in a park can provide mental and spiritual spaciousness.

Give yourself the gift of time to engage in practices that help ground you and sink deep into your center. Encounter the Sacred that dwells there. The Goodness that cannot be overcome.

Move Forward

In a New York Times opinion piece “How Not to Fall Into Despair,” Brad Stulberg quotes Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl and uses his term “tragic optimism.” It involves acknowledging pain and hardship and in the face of it, moving forward in a positive way.

It’s the “both/and” stance central to many religions, including Christianity. Jesus lived acknowledging and confronting the evils of his day while still finding room in his heart to hold love, forgiveness, and hope.

He lived compassionate engagement, hanging out with the marginalized and calling his followers to care for the poor, widows, and orphans. Love God and your neighbor as yourself, he said. He didn’t list exclusions. He didn’t ignore the oppressors in power but didn’t let fear paralyze him.

What is mine to do?

One friend said she was taking the “left foot, right foot, left foot, right foot” approach. Not looking into the future but being present to the moment and to what she could do where she was, to put kindness and compassion into the world. Another is concentrating on volunteering for organizations that serve others in her city. Both are claiming agency rather than helplessness.

It involves what Stulberg calls “wise hope and wise action.” Not hope born of denial, thinking that if we just wait long enough, things will get better, but seeing things for what they are and still taking action.

In his final written message published in the New York Times after his death, the great civil rights activist John Lewis charged us to do that. To stand up and speak out when we see something that isn’t right. “Democracy is not a state.” He said. “It is an act.”

I am overwhelmed by what is happening. I feel helpless. But I’m not. I can do what I can do where I am. I can write. I can be kind to strangers and the marginalized. I can donate to organizations that support causes I believe in, especially those that serve targeted populations threatened by the wave of “othering” spreading across the country. I can stay informed, write to Congressional representatives. I can speak up to representatives in my state government when they propose and pass legislation that demonizes and oppresses monitories.

Darkness doesn’t have to win in the long run. Not when enough people inject the light of love and compassion into the night.

What is yours to do? How can you claim agency and move forward?

The Long View

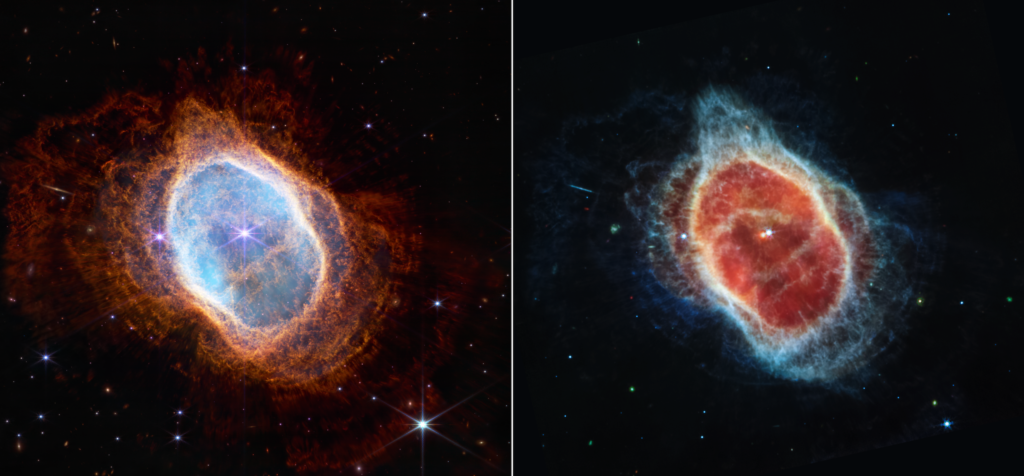

Recently I stood with a woman on the beach, both of us looking across the ocean. “Stay connected to nature,” she said. “It will help with the long view. It will give you strength. It endures.”

Sitting in the National Gallery of Art in front of two van Gogh masterpieces I remembered that people suffering in all kinds of ways throughout history have been able to see beauty and hope through their grief and found ways to share it with the world.

In dark times, I find it difficult to believe that the moral arch indeed bends toward justice. But Viktor Frankl, John Lewis, and countless others, known and unknown, did. And they knew the truth of that saying depends on individual action. They lived holding both grief and hope in their hearts and found courage to move on.

Jesus did. Those who strive to imitate his life, to follow his Way, will too. It’s not a “Christianity” that storms the Capitol with violence when things don’t go your way. It’s not a “Christianity” that sees some people as expendable and deserving of disrespect. It strives to serve the common good. It’s a both/and faith. It’s a grief/hope faith. It doesn’t deny pain, oppression, and suffering. Jesus wept over Jerusalem. But he kept on going, living with compassion.

May it be so.

Sources

Together, You Can Redeem the Soul of Our Nation by John Lewis

How Not to Fall Into Despair by Brad Stulberg