Full disclosure: I’ve tried to write this column for weeks. Thoughts and notes spill across my journal pages; drafts of documents sit on my laptop. Prayer and vigil candles are spent. Life feels heavy. Sometimes overwhelming. The state of our world and our country is revealing the dark, shadowy side beneath our comfortable façade. And cracks in that façade are everywhere.

Full disclosure: I’ve tried to write this column for weeks. Thoughts and notes spill across my journal pages; drafts of documents sit on my laptop. Prayer and vigil candles are spent. Life feels heavy. Sometimes overwhelming. The state of our world and our country is revealing the dark, shadowy side beneath our comfortable façade. And cracks in that façade are everywhere.

Leonard Cohen’s lyric from Anthem comes to mind: “There is a crack, a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.” True enough. But cracks can also make things fall apart – as some must do – before they are put back together or something new is made. In the process, it’s often the cracks we see, not the light.

You may find that true today. The world struggles to find responses to climate change and the will to implement them. The the pandemic brings not only sickness and death, but economic crisis, causing millions to struggle to survive. It challenges the world’s “normal” which, really, hasn’t been working all that well.

Our country, fractured by political turmoil, division, and fumbled responses to COVID-19, must also recognize the racism that is staring in our collective face. The video of George Floyd’s murder by policemen was a tipping point, coming closely on the heels of other senseless murders of African Americans. Protests erupted across the U.S. and the world and continue today. They must. They make us look. They reveal cracks that have crazed our nation even before it was born.

“What can I do?” I ask myself. I don’t have answers; I have questions. It’s time for white people to look deeply at their own stories and those of their ancestors and recognize how they have benefited from systemic racism for generations. We can educate ourselves. Reading and discussing the book Waking Up White: And Finding Myself in the Story of Race by Debby Irving, is jarring as our group listens to the long history of racism and slavery in our country from the beginning, hearing how early it was codified into our laws.

Truth illuminates the cracks. It’s the light that gets in. And once it does, we have a choice. The line before Cohen’s famous one quoted above is this: “Ring the bells that still can ring. Forget your perfect offering.” Our efforts will not be perfect, but they must be made.

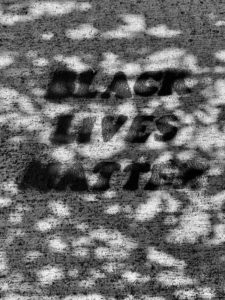

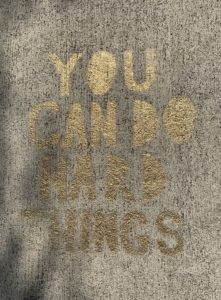

We all must do the hard work of hearing the truth and making changes in our lives and in the laws and practices of this country. On a walk in my neighborhood I noticed two messages painted on the sidewalk: “Black Lives Matter” and “You can do hard things.”

These unprecedented times demand we recognize the truth of both. There is much in our world and in our nation that requires doing hard things for the good of all.

This year, July 4 presents an opportunity to reflect on our country, to consider its history through an inclusive lens, and to work for its future. When I pondered the Roman Catholic Lectionary readings for this holiday, the one from Philippians spoke to my heart:

Finally brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence and if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things…

It is hopeful. It reminded me to look for what is good in the world, in one another, in our dreams and values. To focus on justice and truth. To hold tight to them. To look for the light coming in through the cracks.

But that wasn’t all. The reading continued:

Keep on doing what you have learned and received and heard and seen in me.

What have we seen in Jesus? Love. He was all love. Love of God. Love of neighbor. He stood with the poor and marginalized. He challenged those who abused power and were greedy, concerned only with their own comfort and well-being. He told the Good Samaritan story: everyone is our neighbor; we must take care of one another. He never saw anyone as “other.” Everyone belonged. In the end, he was murdered by a world that couldn’t accept such radical, inclusive love.

This reading calls us to hope and also to act, like Jesus, keeping our hearts set on what is good and just. On Love. To use our hands and feet and minds and talents to bring more of it into this world. And, as the reading ends, Then the God of peace will be with you.

©2020 Mary van Balen

On Ash Wednesday I took tentative steps into the Lenten season. I wasn’t sure what disciplines to embrace, but that morning I lit a candle and sat quietly in prayer before going through liturgical readings for the season. I attended a noon service and stood in line to receive ashes on my forehead, remembering that I was dust and someday, to dust would return.

On Ash Wednesday I took tentative steps into the Lenten season. I wasn’t sure what disciplines to embrace, but that morning I lit a candle and sat quietly in prayer before going through liturgical readings for the season. I attended a noon service and stood in line to receive ashes on my forehead, remembering that I was dust and someday, to dust would return.