… And my heart panics not to be, as I long to be, / the empty, waiting, pure, speechless receptacle.

Mary Oliver from poem “Blue Iris”

Today, I stood on the porch and drew draughts of cold air deep into my lungs, happy for it after two days spent mostly inside. Raindrops made linking circles, expanding and disappearing at the edges of driveway puddles. I remembered a column written years ago in which I named rain an icon of God’s ever-present Grace soaking our souls. Looking out at the morning, I prayed to be open to it. And I thought about yesterday’s gift – the lunar eclipse.

Unable to sleep, I had risen around 1 a. m., brewed a pot of Red Rose, and pulled a small panettone intended for the holidays from its hiding place in the pantry. The sweet bread, studded with raisins and candied orange bits, melted in my mouth. Enveloped in a fleecy robe and a wing-backed chair, I read poetry and sipped the tea.

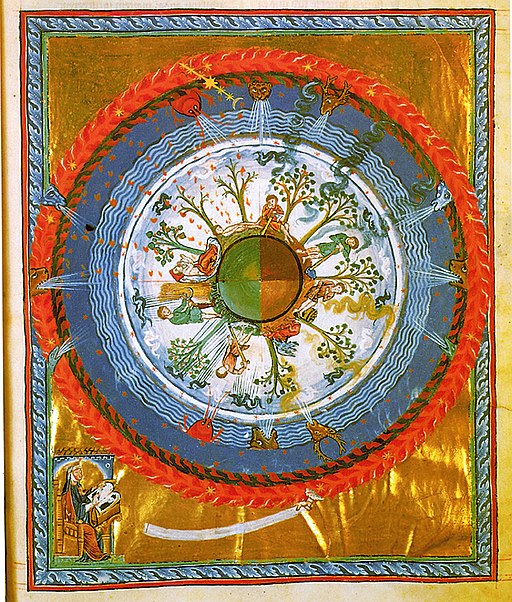

The longest partial lunar eclipse in a millennium was approaching. Off and on I put down my book and mug and walked out onto the driveway. The unusually crystal-clear sky was stunning. Orion’s shoulders angled toward the moon, still white and whole. Later it would begin to move into the earth’s shadow.

Returning to the kitchen, I decided to make cornbread for the morning. Soon the baking wholegrains filled the house with earthy aromas. I knew I wouldn’t wait till the morning to eat a slice. “It is morning,” I told myself as I buttered a bit. “Very early morning!”

More tea. More poetry. I watched the moon as darkness began to take a bite out of it around 2 a.m. At 3, I crawled back into bed, setting my alarm for 4, mid-eclipse, when the earth’s shadow would drape the moon with a reddish orange veil.

The hour passed in a blink, and I was back outside: a grey-haired woman in her robe and slippers, cradling a large mug in her hands. Standing with Orion and whatever other stars and creatures were witnessing the moment, I lifted my mug and sipped tea, a toast to the moon. Not quite a complete eclipse, but I think even more beautiful because of it. The tiny crescent of brilliance near the base held the rusty moon as if in a thin, silver cup.

Give praise, sun and moon, / give praise, all you shining stars! / Give praise all universes, / the whole cosmos of Creation!

Psalm 148 translation: Nan C. Merrill

“Receiving blessings with gratitude,” a friend said, “requires humility.”

Gazing out into our solar system, overwhelmed by the sight, I longed to be an ever-open receptacle of such beauty. It spilled out over me, the pavement, gnarled trees, and blades of grass. Grace opens one’s eyes to the extraordinary reality of everyday things and to the Presence that dwells in all.

The immensity of the cosmos in which our earth spins, humbled me, and I gave thanks, adding my small voice to the chorus of praise rising from all creation. Astronomical events always provide needed perspective. Disheartened as I felt that night about events in our country and world, I was reminded that I see only a snippet of what is happening. That life continues to evolve and change. That my moment is not the only moment. There is a long view that I do not have. I want to trust that it is bending toward justice. But some nights, I don’t.

That night Orion, the moon, and the magnificence of creation nudged me towards faith and courage.

Finishing my tea, I walked back inside and returned to bed. Hope cautiously emerging from the edges of my mind, and a prayer of gratitude stirring in my heart.

© 2021 Mary van Balen

Feature photo by Mary van Balen – Stained-glass dome of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri in Rome. Architect: Michelangelo