Sunday night, May 15, I slept through a total lunar eclipse. Usually, I send email reminders to family and friends a day or two before the event. When the night arrives, I set my alarm and stand on my driveway or in the backyard at any hour, no matter how late, to witness the cosmic display. Eclipses, lunar and solar, have inspired several posts on this blog in the past. (See here, here, here and here.) How’d I miss this one?

I didn’t notice the date on my wall calendar or date book. (Yes, I still use the paper ones.) I passed over the EarthSkyNews1 email alert. I even missed the second text sent that night on our family thread. I saw the first, at 10:02. Uncharacteristically, I was already in bed. “Don’t forget to check out the Blood Moon tonight,” it read. I pulled off the sheet and walked outside to look. It’s edges and light were softened by misty, wispy clouds, but the full moon was just clearing the apartments across the street, headed for open sky above. The text reference to “Blood Moon” was lost on me. The pale orb looked lovely, but nothing red about it. After five minutes or so, I headed back to bed and to a long night of much needed sleep.

When I awoke late Monday morning, I reached over to the bedside bookcase, pulled off my phone and reading glasses and checked for messages. (I’m way too tied to that phone!) Ah. There was another from Sunday night. It arrived at 10:04 pm while I was out in my PJs and bare feet looking at the moon. “The partial eclipse begins at 10:30.” There it was.

A matter of two minutes made the difference between my watching a stunning total lunar eclipse and my sleeping peacefully away for ten hours! “I needed the sleep,” I rationalized, but didn’t feel any better about missing the experience.

The dance of planet, moon, and sun governed by laws of physics never disappoints. Sunday night, the full moon blushed a deep red as it moved into the earth’s shadow. With feet planted on the ground, anyone with a clear sky above could have looked up in wonder at the spectacle that played out nearly 240,000 miles away. It was glorious—whether or not celebrated by human beings.

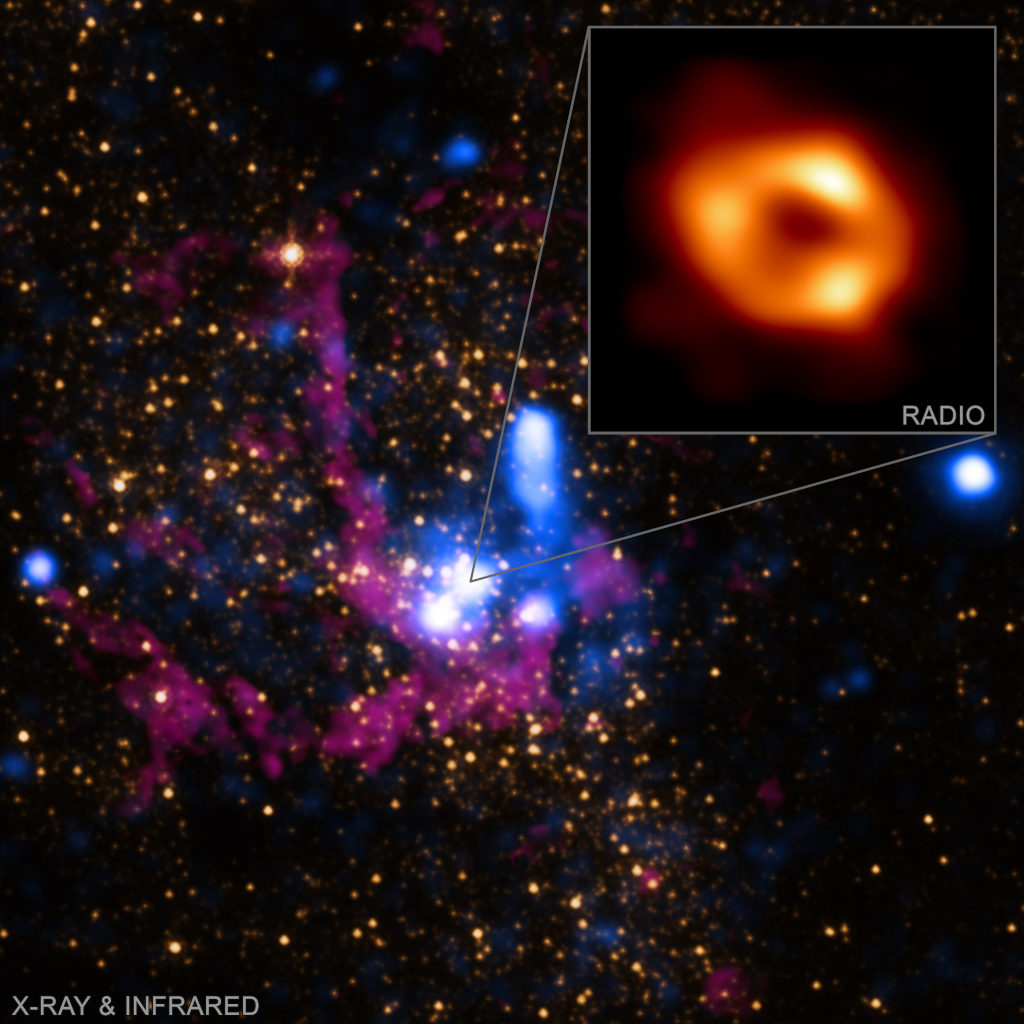

Creation continues to do what it has been doing for eons, regardless of our attention—evolving, expanding, birthing new stars, galaxies, and realities we can’t imagine. It’s a work in progress. Occasionally the veil of distance, time, and space is drawn back just a bit, and we catch a glimpse. (Did you see the first photo of the black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy2?

As I lamented my missed opportunity, I thought of Psalm 27 that reminds us that God’s grace comes even as we sleep and took some comfort in the knowledge that beauty released into the universe blesses even when unnoticed. The splendor of the Blood Moon, the incredible workings of our solar system that produced it, the ongoing evolution of the cosmos in which we live, are all expressions of Love constantly given away.

A child asleep in her mother’s arms is no less loved than when the little one is awake and aware of the affection. My sleeping through the eclipse didn’t diminish its wonder. As I slept those ten hours away, I rested, cradled in the arms of the universe and the creative arms of the Mother-God in whom it unfolds.

Awareness doesn’t change the reality of Love-shared, but it can enlarge the hearts of those who notice with appreciation and openness to receive.

In Mary Oliver’s long poem “From the Book of Time,”3 she writes of beginning a spring day at her desk but being drawn by birdsong into the outdoors where she noticed the grass and butterflies moving above the field.

“ … And I am thinking: maybe just looking and listening / is the real work. // Maybe the world, without us, / is the real poem…”

Surely, the cosmos doesn’t need us to be what it is, to be the “real poem.” Yet since we are here, we are invited to help with the composition: a word, a phrase, a comma or full-stop. We contribute, knowingly or not. How and what depends on each of us. A bit of glory here, a bit of sorrow there. Love. Hate. Compassion. Fear.

While I trust in Holy Presence, whether cognizant of it or not, I will pay more attention to special events that can open my heart and the eyes of my soul. November 8, the next total lunar eclipse of this year, is already circled on my paper calendars. I might even add an alert on my phone.

Meanwhile, no need to wait for an eclipse. The universe is always spilling over with unfathomable creativity. The jots we are privileged to witness point our minds and hearts toward the Holy Mystery that is far beyond comprehension but is the life force in all that is. This Mystery showers us with goodness and love, even if we, unaware, sleep right through it.

Sources:

1 Subscribe to EarthSkyNews newsletter

3 “From the Book of Time” in Devotions: The Selected Poems of Mary Oliver, p. 234

More info on the Black Hole: Sagittarius A

The Milky Ways supermassive black hole

Here’s How Scientists Turned the World Into a Telescope (to See a Black Hole)

Black Hole Image Makes History

Feature image by Ulrike Bohr from Pixabay