On this feast of the Ascension, I offer the reflections of two Catholic’s on the subject, one a theologian and the other a specialist in the fields of spirituality and systematic theology. The first is Karl Rahner, a German Jesuit whose contributions including those at Vatican II have made him one of the most influential theologians of the twentieth century. In the book The Great Church Year: The Best of Karl Rahner’s Homilies, Sermons, and Meditations, he writes of the gift of the Spirit which is the gift of the Ascension. Though through his leaving Jesus seems to be removed from us, he is really closer to us than he could have been in the flesh: He dwells within us in the Spirit.

On this feast of the Ascension, I offer the reflections of two Catholic’s on the subject, one a theologian and the other a specialist in the fields of spirituality and systematic theology. The first is Karl Rahner, a German Jesuit whose contributions including those at Vatican II have made him one of the most influential theologians of the twentieth century. In the book The Great Church Year: The Best of Karl Rahner’s Homilies, Sermons, and Meditations, he writes of the gift of the Spirit which is the gift of the Ascension. Though through his leaving Jesus seems to be removed from us, he is really closer to us than he could have been in the flesh: He dwells within us in the Spirit.

“We notice nothing of this, and that is why the ascension seems to be a separation. But it is a separation only for our paltry consciousness. We must will to believe in such a nearness–in the Holy Spirit.

The ascension is the universal event of salvation history that must recur in each individual, in our personal salvation history through grace. When we become poor, then we become rich. When the lights of the world grow dark, then we are bathed in light…When we think we feel only a waste and emptiness of the heart, when all the joy of celebrating appears to be only official fuss, because the real truth around us cannot yet be admitted, then we are in truth better prepared for the real feast of the Ascension than we might suppose.”

Hmm…How does that work, in my life? In yours?

It has to do with the percieved dichotomy: If one is poor, one cannot be rich, right? In this case, wrong. Being poor, deprived of the earthly presence of Jesus, in fact makes us rich because the Spirit comes to live in each of us. Feeling alone and empty can enable us to receive grace and become aware of the Presence within. As one of my favorite poets, Sir Thomas Browne, writes in his poem,

If thou could’st empty all thyself of self:

“But thou art all replete with very thou

And hast such shrewd activity,

That when He comes, He says, `This is enow

Unto itself – `twere better let it be,

It is so small and full, there is no room for me.`

In his book, The Holy Longing,Ronald Rolheiser, the second scholar, presents an interesting way of looking at what Rahner says is the “universal event of salvation history that must recur in …our personal salvation history…” In more colloquial language, Rolheiser says the paschal mystery in our lives is “a process of transformation within which we are given both new life and new spirit.” In this process, the ascension is the time of “letting go of the old and letting it bless you, the refusal to cling.”

In my own life, this has been a very real, sometimes painful part of my ongoing transformational process. One example is my divorce, something as a young Catholic woman declaring her vows before God and community, I never imagined would happen. But it did. It needed to happen, but that did not make “letting go of the old” easy. Sometimes the wounds of those years threatened to overshadow the blessing. Rolheiser’s insistence that the old, no matter what it is, has blessings to give is important to remember. My children, of course, are the first and most important of the blessings. There are others.

“Refusal to cling,” is also important. I had to let go, to feel empty and hurt. The temptation is great to hold on to something, no matter how unhealthy, just because it is familiar. Better the known misery that the unknown…

Not true. As Rahner, Rolheiser, and Browne all remind us, sometimes we must be empty to receive.

The women and men who were Jesus’ disciples surely wanted him to hang around, to have dinner and wine and conversation together; to continue to teach and inspire and lead. Letting go was not easy, but it was necessary. The universal “letting go” is also the universal “opening up” that allows the Spirit to fill us and lead us to new ways of living the gospel message and bringing love and transformation to the world.

PHOTO: Mary van Balen But now ask the beasts to teach you,/ the birds of the air to tell you;/Or speak to the earth to instruct you,/ and the fish of the sea to inform you./Which of these does not know/that the hand of God has done this? Job 12. 7-9 from Morning Prayer

PHOTO: Mary van Balen But now ask the beasts to teach you,/ the birds of the air to tell you;/Or speak to the earth to instruct you,/ and the fish of the sea to inform you./Which of these does not know/that the hand of God has done this? Job 12. 7-9 from Morning Prayer Then Paul stood up at the Areopagus and said: “You Athenians, I see that in every respect you are very religious. For as I walked around looking carefully at your shrines I even discovered an altar inscribed “To an Unknown God.” What therefore you unknowingly worship, I proclaim to you. The God who made the world and all that is in it, the Lord of heaven and earth, does not dwell in the sanctuaries made by human hands, nor is God served by human hands because God needs anything. Rather it is God who gives everyone life and breath and everything…though indeed God is not far from any of us. For ‘In him we live and move and have our being.’ Acts 17.22-25, 27b-28

Then Paul stood up at the Areopagus and said: “You Athenians, I see that in every respect you are very religious. For as I walked around looking carefully at your shrines I even discovered an altar inscribed “To an Unknown God.” What therefore you unknowingly worship, I proclaim to you. The God who made the world and all that is in it, the Lord of heaven and earth, does not dwell in the sanctuaries made by human hands, nor is God served by human hands because God needs anything. Rather it is God who gives everyone life and breath and everything…though indeed God is not far from any of us. For ‘In him we live and move and have our being.’ Acts 17.22-25, 27b-28 PHOTO: Mary van Balen The homily at Mass yesterday included a reference to the pelican and the stained glass window depicting a pelican feeding her young. I first encountered this image in an old university building housing the school of theology. Intrigued by the old ceramic tile with the image of a pelican and her young, I made a rubbing of it in my journal and later asked about it.

PHOTO: Mary van Balen The homily at Mass yesterday included a reference to the pelican and the stained glass window depicting a pelican feeding her young. I first encountered this image in an old university building housing the school of theology. Intrigued by the old ceramic tile with the image of a pelican and her young, I made a rubbing of it in my journal and later asked about it.

PHOTO: Mary van Balen from Volume 4

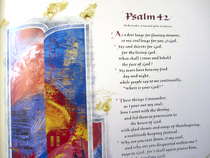

PHOTO: Mary van Balen from Volume 4  As I prayed the Psalter I thought of St. Athanasius (2295-373CE) whose feast was May 2. He is known for his fight against the heresy of Arianism that claimed Jesus was in no way equal to God the Father, having been created, but what I most remember about Athanasius is his wonderful letter to Marcellinus that spoke eloquently of the interpretation of the Psalms. While other books of the Bible are filled with words that inspire or instruct, yet remain the words of the author, words of the psalms are like one’s own words that one read; and anyone who hears them is moved at heart, as though they voiced for him his deepest thoughts.

As I prayed the Psalter I thought of St. Athanasius (2295-373CE) whose feast was May 2. He is known for his fight against the heresy of Arianism that claimed Jesus was in no way equal to God the Father, having been created, but what I most remember about Athanasius is his wonderful letter to Marcellinus that spoke eloquently of the interpretation of the Psalms. While other books of the Bible are filled with words that inspire or instruct, yet remain the words of the author, words of the psalms are like one’s own words that one read; and anyone who hears them is moved at heart, as though they voiced for him his deepest thoughts. When I hold the old Psalter in my hands and pray the words printed there, I am connected not only with my monk friends, but also with my ancestors. I am in touch with my heart, and my journey and the God who embraces us all.

When I hold the old Psalter in my hands and pray the words printed there, I am connected not only with my monk friends, but also with my ancestors. I am in touch with my heart, and my journey and the God who embraces us all. Supermoon, May 5, 2012 I wish I had a photo of the campfire, of someone holding up jumbo marshmallows flaming on the end of a stick looking like a torch, or another women eating the gooey treats like a drumstick. Or a photo of a woman sitting by the pond casting and catching fish into the night. Or of the supermoon edging the dark rain clouds with silver and then emerging glorious and bright.

Supermoon, May 5, 2012 I wish I had a photo of the campfire, of someone holding up jumbo marshmallows flaming on the end of a stick looking like a torch, or another women eating the gooey treats like a drumstick. Or a photo of a woman sitting by the pond casting and catching fish into the night. Or of the supermoon edging the dark rain clouds with silver and then emerging glorious and bright.

Could it be that the faithful might have a theological intuition that diverges from the Churchs teaching and that they might be right? It wouldnt be the first time. Blessed John Henry Newman thought so. He had studied the history of the Arians and used some of that history in his article, On Consulting the Faithful on Matters of Doctrine. Newman pointed out that the Arian heresy was defeated not by bishops or popes, most of whom supported the Arian position. The faithful, mostly the laity, were the ones who steadfastly held to the truth of the divinity of Jesus, sometimes at the cost of their lives. It was the consensus fidelium or consent of the faithful that saved the day.

Could it be that the faithful might have a theological intuition that diverges from the Churchs teaching and that they might be right? It wouldnt be the first time. Blessed John Henry Newman thought so. He had studied the history of the Arians and used some of that history in his article, On Consulting the Faithful on Matters of Doctrine. Newman pointed out that the Arian heresy was defeated not by bishops or popes, most of whom supported the Arian position. The faithful, mostly the laity, were the ones who steadfastly held to the truth of the divinity of Jesus, sometimes at the cost of their lives. It was the consensus fidelium or consent of the faithful that saved the day.

PHOTO: Mary van Balen One day last week and friend and I were walking through a small woods near my home.

PHOTO: Mary van Balen One day last week and friend and I were walking through a small woods near my home.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin May 1, 1881-April 10, 1955

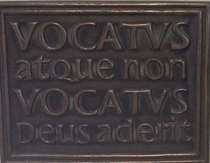

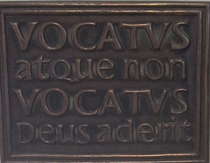

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin May 1, 1881-April 10, 1955  This morning, the beginning of a day off work, I walked into my office, lit two candles while singing the old hymn, “Come Holy Ghost,” and sat facing the small collection of sacramentals surrounding the Bible. Having long neglected the practice of Lectio Divina and quiet prayer, I came again to, if nothing else, rest in the presence of God. The plaque above the bookcase reminded me that on the days I do not do this God is no less present to me. (Called or not called, God is present.)

This morning, the beginning of a day off work, I walked into my office, lit two candles while singing the old hymn, “Come Holy Ghost,” and sat facing the small collection of sacramentals surrounding the Bible. Having long neglected the practice of Lectio Divina and quiet prayer, I came again to, if nothing else, rest in the presence of God. The plaque above the bookcase reminded me that on the days I do not do this God is no less present to me. (Called or not called, God is present.) As Telihard says, we must “See or perish.” We must see Christ in one another. We must seek unity and solidarity, not division and discord. We must stand with those who are marginalized and remember that we move forward together or not at all.

As Telihard says, we must “See or perish.” We must see Christ in one another. We must seek unity and solidarity, not division and discord. We must stand with those who are marginalized and remember that we move forward together or not at all.  PHOTO: Mary van Balen

PHOTO: Mary van Balen

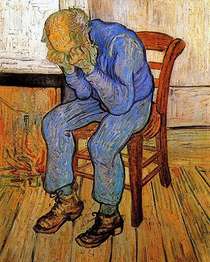

“Sorrow” by Auguste Rodin 1881-1882 Reading

“Sorrow” by Auguste Rodin 1881-1882 Reading  Again the news surfaces during Holy Week, when Good Friday offers theGood Friday offers an opportunity for the Church to admit wrongdoing, repent, and ask for forgiveness, as all Christians are encouraged to do. Will this Good Friday pass as it did two years ago without church hierarchy taking advantage of it? I imagine so. Until it is grasped, and Church leadership is honest with itself and with the world, its credibility is lost and more faithful will find other communities to join for worship and Christian life.

Again the news surfaces during Holy Week, when Good Friday offers theGood Friday offers an opportunity for the Church to admit wrongdoing, repent, and ask for forgiveness, as all Christians are encouraged to do. Will this Good Friday pass as it did two years ago without church hierarchy taking advantage of it? I imagine so. Until it is grasped, and Church leadership is honest with itself and with the world, its credibility is lost and more faithful will find other communities to join for worship and Christian life.